Sirica and Nixon: A High Stakes Contest Over Executive Privilege

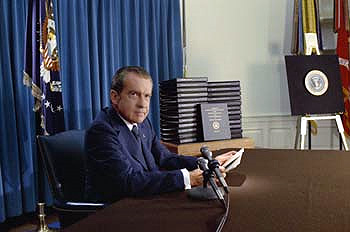

In the summer of 1973, faced with a grand jury subpoena demanding that he turn over tapes of Oval Office conversations thought to relate to the Watergate investigation, President

Richard Nixon L ’37 responded with a personal letter to the presiding judge, John J. Sirica of the District of Columbia district court.

In the summer of 1973, faced with a grand jury subpoena demanding that he turn over tapes of Oval Office conversations thought to relate to the Watergate investigation, President

Richard Nixon L ’37 responded with a personal letter to the presiding judge, John J. Sirica of the District of Columbia district court.

“I must decline to obey the command of that subpoena. In so doing I follow the example of a long line of my predecessors who have consistently adhered to the position that the president is not subject to compulsory process from the courts,” the president wrote in his letter dated July 23, 1973. He claimed that all communications he had with his aides were privileged, and that executive privilege was absolute.

The president’s letter regarding the tapes that ultimately brought down his presidency was donated to his alma mater on November 21, a gift of Judge Sirica’s son, John Sirica, Jr., T ’76.

“I am honored to give this letter to Duke Law School,” Jack Sirica, a Newsday editor, said in making the presentation. “My dad was a great fan of the School and a close friend of [former] Dean Ken Pye. [Duke] did great things for me.”

Before an audience of Duke Law students, faculty, and friends, Sirica shared his father’s concerns over the subpoena, which for the first time compelled a sitting president to turn over evidence in a criminal investigation. While the judge knew the criminal courts “inside and out,” constitutional law was less familiar, and he feared making a mistake, said Sirica. But when his father polled the 12 members of the grand jury, and they all agreed the subpoena should be enforced, “he thinks, ‘I’m sitting here with 12 people from various walks of life from Washington, D.C., and they’re compelling the president to turn over evidence.’ And, as he used to say, what a great country it is.”

Charles S. Murphy Professor of Law and Public Policy Studies Christopher Schroeder noted that for public lawyers, “the most riveting aspects of the Watergate investigation involved the constitutional confrontation between the president, the courts, and the Congress that had preceded it,” making the letter, which effectively launched the landmark case of U.S. v. Nixon, a particularly significant gift.

By July 1973, Schroeder said, the investigation into the 1972 break-in at the Watergate Hotel headquarters of the Democratic National Committee had intensified, in spite of the burglary convictions of seven relatively low-level operatives of the committee to reelect the president. When a White House employee, Alexander Butterfield, disclosed to a Senate committee on July 16, 1973, that the White House had a taping system, “the investigation really began honing in on what the president knew and when he knew it,” said Schroeder.

At that point, the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, went to the grand jury and quickly obtained from Judge Sirica a subpoena asking the president to turn over tape recordings of particular conversations in the Oval Office.

Following the delivery of his letter to Judge Sirica, the president mounted a formal court challenge. The judge’s refusal of a motion to quash the subpoena was upheld on appeal, and the U.S. Supreme Court convened a special summer session to hear the matter on an expedited basis–though not before the president had notoriously ordered the firing of Special Prosecutor Cox for refusing an offer to have a senator provide transcripts of the tape. That move, Schroeder said, was fully in keeping with the president’s view that all the powers of the executive branch were held by the president alone; Cox was his subordinate who had to follow his orders or be terminated.

While the Supreme Court recognized the president’s claim of executive privilege in a unanimous decision, it did not find it absolute, Schroeder pointed out. In the circumstances, the privilege gave way to the superior constitutional claim of the district court and the criminal trial proceeding there. “The Court also left many other questions open, many of them being debated today, using the basic frameworks on the one hand that President Nixon laid out in his letter, and on the other hand, that the special prosecutor defended in his briefs and arguments,” he said.

Among the tapes released to the special prosecutor following the Supreme Court decision was the “smoking gun,” a recording of the president and aide Bob Haldeman, talking of ways to subvert the break in investigations and stage a cover up. In August, 1974, President Nixon resigned.

“The critical issues were being driven by actions taken in a single federal courtroom by John Sirica, a federal judge who reached conclusions that disagreed with the president, and had the courage to stick to those convictions,” said Schroeder.

President Richard Nixon’s letter to Judge John Sirica will be part of the permanent collection of the Duke Law Library, and will be housed at Duke’s Special Collections Library, said Archibald C. and Frances Fulk Rufty Research Professor of Law Richard A. Danner. “The letter is important not just for its historical and legal significance, but also because of President Nixon's connections to the Law School.”