Ember Reichgott Junge '77

As a Minnesota state senator, Ember Reichgott Junge spearheaded the passage, in 1991, of the nation’s first charter school law. She recalls feeling “personally devastated” as a bruising three-year legislative battle came to an end.

“The bill was severely compromised in the conference committee and, as passed, I thought it was so weak that a charter school would never open,” she admits more than 20 years later, recounting the massive opposition her bill met from teachers unions and members of her own Democratic-Farmer-Labor party, and the legislative gymnastics used to pass it.

“I had to accept the compromise because I knew we would never get another chance — the resistance was too great,” she says. “A colleague taught me a great lesson: ‘Ember, just remember: Pigs get fed and hogs get slaughtered.’ I had to take the weak compromise. Even then it passed by only three votes — with the help of a bipartisan coalition from the center.”

Her doubts weren’t realized. The first charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992 and a movement grew; as Reichgott Junge points out, more than two million students now attend charter schools across the country. She cites a September 2012 Kappan/Gallup poll indicating that two-thirds of the American public supports chartering.

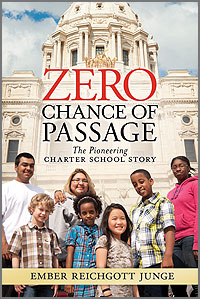

“What else does two-thirds of the American public support in this divided political climate?” Reichgott Junge says with a laugh. But she also acknowledges ongoing controversy surrounding the charter school movement, designed, she says, simply to afford parents and teachers the autonomy to operate public, independent schools in return for specifically contracted performance results. She hopes, in part, to set the record straight with her new book, Zero Chance of Passage: The Pioneering Charter School Story (Beaver’s Pond Press, 2012), where she shares her personal journey of pioneering chartering through its origins, legislative passage, and into the robust national public education debate.

“What else does two-thirds of the American public support in this divided political climate?” Reichgott Junge says with a laugh. But she also acknowledges ongoing controversy surrounding the charter school movement, designed, she says, simply to afford parents and teachers the autonomy to operate public, independent schools in return for specifically contracted performance results. She hopes, in part, to set the record straight with her new book, Zero Chance of Passage: The Pioneering Charter School Story (Beaver’s Pond Press, 2012), where she shares her personal journey of pioneering chartering through its origins, legislative passage, and into the robust national public education debate.

Making legislative history

On her election to the state Senate in 1982 at the age of 29, Reichgott Junge was appointed to both the Judiciary Committee — she was the first woman to sit on that committee, which she later chaired — and the Education Committee. “Education was a passion of mine,” she says. “I was a proud product of our public schools and worked closely with teachers in my election.” She sponsored into law the nation’s first open-enrollment statute, initially proposed by Gov. Rudy Perpich in response to a national report calling for improvements to public education. It became law in 1988.

“Open enrollment was a national breakthrough in public education, because it was the first time public school students could choose to attend any public school in the state. They didn’t have to stay in their home districts. The option was immediately popular,” Reichgott Junge says. “But once we had more access to choices, what if all the choices were the same? We needed more choices to access. So we started thinking about creating more and different [school] choices for children, particularly in their own neighborhoods. Open enrollment was fine, but only people with resources could transport their children across town to another school.”

A task force of civic leaders addressing school improvement issues offered chartering as a viable option, she explains, as a way to incent the public K-12 system to become more responsive to change, and to empower teachers who felt constrained by the dictates of school districts. “Chartering, by definition, allows someone other than the public school district to deliver public education. That provides more choices for students and stimulates responsive change in the larger system.” It worked, says Reichgott Junge. “Many K-12 districts have responded to charter schools in their neighborhoods with new options requested by parents and teachers.”

Joining a national movement

Reichgott Junge facilitated various improvements to Minnesota’s pioneering charter school law in subsequent legislative sessions. It was protected against repeal, she notes, by the national conversation on charter schools — as a public school choice alternative to private-school vouchers – that exploded within weeks of the law’s passage. And although she did not know it at the time, Gov. Bill Clinton had been pointing to Minnesota’s law as a model for chartering as he campaigned for his first term as president.

She never anticipated being involved with the issue for the long term. She enjoyed a long career as a corporate lawyer before joining the nonprofit sector in 2007, and currently serves as vice president of strategic outcomes for People Incorporated, a mental health services nonprofit. But controversy and misconceptions arose around charter schools by the time she retired from the legislature in 2000. “Charter schools were being perceived as far right in some states and far left in others,” says Reichgott Junge. She became involved on a volunteer basis with national chartering organizations, and wrote her book to clarify the goals of chartering and inform its future.

“We need to strengthen the quality and accountability [of charter schools] with strong authorizers, skilled school leaders, and well-trained charter school board members, among other things,” she says. “Charter schools have always been expected to do more with less, but that funding gap is becoming unsustainable in some places. I hope my book can refocus the national conversation in part on these issues.”

Lessons learned

Reichgott Junge is also eager to share lessons that still resonate today from the legislative push for charter schools, which earned her a 2000 Innovations in American Government Award from Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government; she also was inducted into the National Charter Schools Hall of Fame in 2008.

“The first lesson is ‘Compromise is not defeat,’” she says. “Compromise was the only way the bill could pass, and it provided a firm foundation for a system redesign lasting over twenty years. Without compromise, we might not have charter schools today.

“The second lesson is ‘There is more than one right answer.’ In today’s policymaking, we have only ‘right and wrong’ — we don’t have a ‘next right answer’ where we build on each other’s ideas to come to resolution. That’s governing at its best — and we can return to that! I hope today’s Duke Law students will bring back that kind of policymaking by becoming tomorrow’s policy entrepreneurs.”

Including outside points of view is a third key lesson for policy development, she observes. “The civic leaders involved in the original chartering discussions were true policy entrepreneurs. They came from business, labor, nonprofits, and other areas of civic life and were willing to help legislators think through important issues and move their thinking ‘outside the box.’”

Finally, bipartisanship was central to the launch of the charter movement and is sorely needed in today’s political climate, Reichgott Junge says. “Chartering would not pass today, in most states or in Congress, because we are too divided and too partisan. Chartering came from the middle of the political spectrum — even from outside the political spectrum — and was passed with a true bipartisan coalition. That is why it has sustained for 20 years.”