Q&A with Newsmakers

Center for Sports Law & Policy Co-Director Doriane Coleman speaks with Olympian Edwin Moses

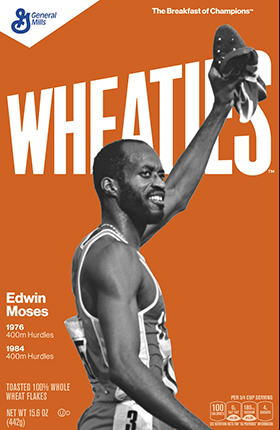

Edwin Moses is one of the most recognized and widely respected athletes in the world. He is a four-time Olympian ('76, '80, '84, '88), two-time Olympic gold medalist ('76 and '84), two-time World Champion ('83 and '87), and former world recordholder in the 400 meters hurdles, with a personal best of 47.02. With a B.S. in physics, an MBA, and an honorary doctorate, Edwin is also a pioneer in the global anti-doping movement, the chairman emeritus of the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), and a former member of the Executive and Education Committees of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). At the end of this year he wraps up twenty years as the inaugural chairman of the international Laureus Sport for Good Foundation, whose academy is comprised of "a unique group of sporting legends, each of whom reached the very highest level of achievement and collectively created many of sport's most iconic moments."

Edwin and I have collaborated on a number of projects over the years, including on the development of the world's first random, out-of-competition drug testing program for what is now USA Track & Field; on a white paper detailing the outlines of what would eventually become the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), as part of the 1999 Duke Conference on Doping; and on a short-lived sports agency called The Platinum Group. Here, among other things, we talk Sha'Carri Richardson and Katie Ledecky, the physics of his performances and his extraordinary win streak, the Russia investigation and Olympic Movement politics, the role of sports stars in promoting athletes' rights and anti-racism, the pre-Nike days of Adi and Rudy Dassler, and the Olympics and Olympians in the geopolitical arena.

At the end of my last conversation with Mike Joyner from the Mayo Clinic, Mike talked about what makes Katie Ledecky so good—from his point of view she's up there with just Secretariat as the greatest endurance athletes of all time. Part of his explanation was that, like you and your famous 13 steps between hurdles, she's figured out how to be exceptional technically, especially under water on the turns. Mike asked me to ask you what you think of Ledecky and his comparison.

He's absolutely right. There's no doubt she's solved a really big equation, mastering both the mechanics of her events as well as being in top condition.

The strength and endurance piece for her is about getting up and swimming thousands of thousands of meters every day, multiple times a day, to get basic strength. With running, you're only dealing with the weight of the air around you, which is pretty light compared to water. Water is a huge mass of material in comparison. The dynamics of pushing that much mass out of the way, she's like a bodybuilder or a weightlifter. My number one concern at the beginning of the season was conditioning and endurance. I ran everything from 4.5 courses to 2 miles in the sand at the beach, and 1000 meter runs in the grass and repeat 1000s and 800s on the track. I also did hour long runs with Henry Rono on the golf course. Because of this, I was totally in tip-top condition by the time I transitioned to shorter, faster runs in the middle phase of the annual training cycle, where I was taking that endurance and using it to build power.

The mechanics piece for Ledecky is about the angle that her hands hit the water, the way she's pushing underwater, including for her on the all-important turns. Mike's analogy to my 13 steps is right. Like Ledecky's turns, which involve pushing as much mass as possible as quickly as possible to streamline the movement, my calculation was designed to reduce the number of times I hit the ground and the amount of time I spent in the air between hurdles. The calculation was completely technical, not just the number of steps, but how you apply them.

Your unbroken win streak of 122 races over 10 years is legendary among athletes and sports historians. Tiger Woods gave you a shout out last year when he was asked about the athletic achievement that most impressed him. I'll throw the same question back at you. Which achievement by an individual athlete, male or female, has most impressed you?

I've never actually never thought about that. If it's about an unbroken win streak, sustained over time, which is what Tiger was focused on, then there's not a lot of comparison. Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic together dominating the highest ranks of men's tennis for as long as they have is impressive, especially because tennis is such a tough sport. To be able to sustain that type of high-level performance, you know, year after year, even when you're into your thirties, I think that's something else.

In your time at the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), as a member of the Executive and Education Committees, the latter of which you chaired, you worked on the Russia investigation and the negotiations over the terms of Russia's return to good standing within the Olympic family. Can you summarize the political tensions among the Olympic Movement organizations that have made those negotiations so difficult?

The politics of the IOC is what makes it so difficult, that and the conflicts of interest that exist because members often have multiple significant posts, including with the IOC, WADA, and their original sports federations. Right now, the IOC has the influence it has within WADA because it provides a lot of its funding, so it gets seats on the important committees in exchange. The IOC is invested in Russia being in the arena at the Games and so when IOC members who understand that country's importance are also the ones at WADA who are deciding whether to investigate and sanction it for corruption, it's an impossible situation. You can't serve more than one master. WADA should absolutely be independent of the IOC.

With respect to the Russia investigation in particular, there is a letter in the new USOPC museum in Colorado Springs that USADA head Travis Tygart and I wrote back in 2014, excoriating WADA because of the way that they were handling the case. We were frankly concerned that they were planning to sweep it under the carpet. Our letter demanding an investigation was the catalyst for Dick Pound to launch what eventually became the full-blown Russia probe. Interestingly, when I started at USADA we thought that our only job was to make sure the playing field was level for the athletes in terms of doping. But then about four to five years in, especially after the debacle in Sochi, where the Russians actually switched the samples in the lab and just out and out corrupted the whole concept of the Olympic Games, we had to change our thinking. It's not just about doping and the clean playing field, we're here to actually save sports from itself. We're making sure that both the athletes and the authorities who regulate sport are clean of corruption.

There are maybe a handful of people on the planet who have been involved in drug testing longer than I have at this point. I don't know any with my combined experience, having run an agency, been an athlete, been on the IOC, been on WADA, and who know what the science is about. In all of this time, I've seen a version of the Russia debacle three or four times. To see it happening again and again is really heartbreaking, not only for me, but for athletes around the world.

From the point of view of the sports authorities, what were the pros and cons for the United States of putting Sha'Carri Richardson on the relay?

There were no real pros to doing that. The basic theory of the US Olympic trials is that they alone can qualify an athlete for Team USA. It's important that people understand that we're completely committed to this theory because of the depth of our talent pool in this country and because the process mimics what will happen at the Games. In Sha'carri's case, her performance was expunged and she was disqualified by the rule violation. It's as though she never crossed the line. The depth point is really important here. Anyone in the 100 meters final and probably one or two who didn't make it to the final are fast enough to comprise a medal-contending relay squad.

Team officials also had to be thinking about the fact that Sha'carri herself said that she didn't want to run the relay. In addition to her own mental state, I'm sure she understood that to bring her into the relay camp after what transpired would have been really disruptive. Who are you going to kick off the team to have her on after a situation like that, English Gardner and Aleia Hobbs? That wouldn’t have been fair at all and the unfairness would have affected the cohesiveness of the group. Cohesiveness is key to getting the stick around the track. They had eight women to pick from, all of them are capable of doing the job. Sha'carri is a couple of tenths of a second ahead of them, but in the relay that's secondary to getting the baton passed safely and efficiently. Because of all of this, if I had been the relays coach, I wouldn't even have entertained it.

As we said earlier this week, we're definitely going to keep looking at cannabis to make sure it makes sense to leave it on the prohibited substances list as it is now, but we can't make exceptions to rule violations just because we really like a particular athlete who happens to be a serious medal contender. That's corruption too.

You recently found an old newspaper clipping in a box in your garage, with the headline "Ed Moses Named in Payoff Probe." The article suggests that both you and Seb Coe – now Lord Coe and the President of World Athletics – were taking under-the-table payments to compete in track meets in England. In other words, that you were being paid to play. Seriously scandalous stuff! What role did you, Seb, and the handful of others in the most elite ranks at the time play in ushering in the modern period where such payments are expected, appropriate, and uncontroversial?

When the story broke, Ollan Cassell – who was the CEO of our federation at the time – asked me, did you sign anything? I said, no. He then told me not to talk to the press, not to admit anything, and just to get out of town. It was harder on Seb and the other British athletes caught up in the scandal because they were at home. But the fact was that European track meets had been paying the top athletes for a long time, back even into the thirties and Jesse Owens. Whatever they said to the general public about amateurism, the federations not only knew all about it, they were involved. The guy who ran and used to pay us to compete in Budapest was also the general secretary of the IAAF. The room you went into to be paid in England was run by people from the British Athletics Association.

They did love to pick on me though. Fifteen or twenty years later, I learned the back story for that article. Apparently, a total of 18,000 British pounds had come up missing from the event budget and meet administrators used me and Seb mainly to cover their tracks. I haven't talked to Seb about it, but I always thought I was doing the right thing. I was on the front lines when it came to getting athletes paid, even though at the time it was for selfish reasons because I was just at the beginning of my career. But at the end of the day, Olympic sport athletes today are being paid to perform, to do commercials, and to earn a living through their sports, not in a back room or under the table. People like me and Tessa Sanderson, Seb Coe and Dwight Stones, and all the others who competed back in the sixties, seventies and eighties, we really pushed the envelope. But I think I was the squeaky wheel at that time. I'll take credit for that.

You were sponsored by Adidas, back in the day when the Dasslers were still alive and doing battle for the world's best athletes and Nike was just a startup called Blue Ribbon Sports. Can you capture something of that Dassler-centered world for us—maybe whatever memory comes to mind first?

If you look at any of the historical films from any of the Olympics in the last century, Adidas was dominant in 1976 and 1972, and probably in '68. There was Adidas, Puma, and I think Asics, those were the only three brands, none of the other brands we know today existed at the time.

Adidas was started by Adolf (Adi) Dassler. His son Horst ran the company in my time. When I first came onto the scene in '76, Horst told me, "You've got to run in Adidas. I have all the best athletes, and that's what I want." He collected the top athletes in the world and treated us correctly, with contracts and whatnot. I was always one of his favorites and as a result, I've been in the shoes my entire life. In fact, I'm doing some work with Adidas right now, renewing my activities with the company.

Both Adidas and rival brand Puma – which was started by Adi's brother Rudi – were based in the same town in Germany, Herzogenaurach. There's a little river and a bridge, one side of the town was Puma. The other side of the town was Adidas. I was in on the right side of town. Horst Dassler lived at the villa on the same property where they also had the factory and an eight-lane running pad where you could test out spikes. I was invited there as his guest many times. He served the best food, cognac, and wine. The first time I had a cognac from 1896 was with Horst Dassler. He was also really introspective in terms of athletes and he loved athletes from foreign countries. He was definitely an equal opportunity employer.

One of the most extraordinary moments in my life in sport was walking down a small side street in Koblenz with you in 1991 or 1992, about 5 years after your last race. As we approached a really old man going in the opposite direction, he looked up and when he realized who you were, his face lit up with a big huge smile and he started stepping rhythmically and then every few steps lifting one of his legs up at an angle. As we crossed him, he said to us excitedly in German, "Thirteen steps, thirteen steps …" and walked on by. You had clearly given him such joy. It was also clear that he was deeply knowledgeable about the sport and your event. Even though US athletes are often among the brightest stars in the international arena, I can't imagine that scene taking place here, except maybe in Eugene or Portland. Why do you think the sport has never managed to be as important in this country as it is abroad?

We have too many sports here in the United States, all the professional sports, all the collegiate sports, everything is so watered down. Elsewhere, especially in Europe, everything is focused on professional soccer and Olympic sports. So people know about biathlon, skiing, modern pentathlon, and so forth. Athletes who win in those sports can be national treasures. In Germany specifically, they don't play American football or baseball, they don't really play cricket, rugby, or basketball. It's all about European football, and track and field and Formula One are next. So basically, there's a lot of focus on Olympians in person and on television. Those are the most valuable properties and it's why we're so popular when we go to Europe.

There's also the history of the rivalries between Germans and Americans. The most famous is probably the rivalry between Luz Long and Jesse Owens back in 1936, when Long helped Owens adjust his stride in the long jump, Owens eventually winning the gold and Long the silver. My parallel was Harald Schmid, who I ran against almost all the way through my career. Harald beat me the first time I ran against him in Germany in 1977 and that was the last race I lost for 10 years. I had a bad day, popped up over a hurdle, took 16 steps instead of 13. I wasn't upset, but I knew I'd never make that mistake again, running so slow that I couldn't use my pattern. The fact that I lived in Germany part time contributed to my popularity there, even though they really wanted Harald to beat me. I was the villain, but a likable villain. Like that old man you remember from Koblenz, they loved me because they knew it was a clean competition and they liked what I was doing on the track. I was so far ahead technically and in terms of results.

A couple of years ago, you invited my colleague Ebony Bryant, Director of Diversity Initiatives at Duke Law, and me to come to Morehouse to speak with students about law school. A few years before that, you hosted our older son Alexander and, on that visit, you made a point of taking him on a tour of the college. You're a proud Morehouse Man, a fact that popped up in one of the most talked about scenes in Spike Lee's latest movie, Da 5 Bloods. What has being a Morehouse Man meant to you personally?

It's meant a lot. I got a scholarship and went for the academics, to study physics and engineering. Just being in that atmosphere around a lot of people who look like me, many who were a lot smarter than me, and in all of that history, it was really inspiring. Even if you grew up without a mother, without a father, or in difficult family circumstances, at Morehouse, as they say, you get and keep "a thousand fathers." You have role models all around you who are constantly on your case to be better. After being in that environment as a student, under the right type of academic pressure, seeing leaders all around you and just being held to a higher standard, it becomes who you are and what you do. You become what pushed and inspired you.

Every man who's ever attended Morehouse has the foundation it takes to be a leader. This includes lots of great students who might slip under the radar in another institution. Employers understand this. Just last week, I introduced a Wall Street company to a group of rising juniors who want to be traders and go into finance. We feel like we're giving our students an extra shot to be and get some things that you just can't find at any other university on the planet.

On that same trip, we went on an after-hours, unannounced tour of the college's private collection of your alum Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s papers and artifacts. I still remember the startled look on the face of its keeper Reverend Dr. Lawrence Carter before he realized that it was you who had disturbed the sanctum—and then his beaming smile and warm welcome. It was evident that you'd spent time there and that civil rights is in your blood. You referenced that heritage in an op-ed you penned in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution – Equality still remains an elusive goal. In that same piece, you also referenced the role of star athletes in the fight against racism. Younger people know about Colin Kaepernick, of course, but he stands on the shoulders of others who came before him. For those who don't know the history, throw out some names … who else should they know?

I definitely want to give a shout out to Reverend Dr. Lawrence Carter, whose office we went into. He is the Dean of the Chapel and the holder of all the important papers and documents, and basically the whole history of Morehouse. He's that guy who, if you want to even take a look at some of those artifacts, they're in his office and in his archives. He's responsible for arranging to get Dr. King's papers to Morehouse.

When it comes to fighting against racism in sport, there are a lot of names most people are completely unaware of. Tell them to look up Curt Flood, Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor, Bill Russell, Walter Beach, Herb Douglas, Harrison Dillard, Mal Whitfield, Tommy Smith, and John Carlos. Herb Douglas was one of my longtime mentors. He died a couple of years ago but even at the end he still talked about how Avery Brundage, who was then president of the USOC, made the Black athletes ride on the bottom of the boat all the way to London to go to the Olympic games in '48. According to Herb, this included Marty Glickman, who was Jewish and on the '36 team. He had to ride down on the bottom of the boat too because Brundage wasn't only a racist, he was also a Nazi sympathizer. Brundage was still president of the IOC in 1968 when Tommy Smith and John Carlos made their stand against racism at the Olympics in Mexico.

It hurts me to have to think that I didn't have to go through what they went through and that it's because of them that I wasn't in a position where I was refused entry into hotels. Black athletes ran track meets in Seattle and other cities around the country where they couldn't stay at the hotels where the white athletes stayed. They paid a tremendous price for me to be able to go forward. This is classic African-American history that no one was taught in most schools, except we learned it at Morehouse.

Also last year, you lead a symposium on the legacy of the US boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow. As a member of Team USA that year, which was during your prime as the #1 ranked 400 meters hurdler in the world, you likely missed out on another chance at Olympic Gold. At the same time, you've always been a student of geopolitics and while it's been central in your life, you appreciate that sport isn't everything. What do you say to those who think that event boycotts – for example of the upcoming Winter Games in Beijing – should be a weapon in the nation's diplomatic arsenal?

I think that politicians should definitely stay out of the Olympics. They want athletes to be politically neutral but then at the first opportunity, they weigh in on virtually everything that goes on at the Games, even though they know nothing about them and make no real financial contributions to the Olympic Movement. For politicians, the Olympics are just a convenient target. Every four years, they recycle a set of themes including racism and discrimination, the local impacts of site selection, pollution. But at the end of the day it's a private business and the athletes have a lot at stake.

It's important to remember this and also that the Olympics are no longer based in the old Pierre de Coubertin white male European model of sport as an amateur gentlemen's game which lends itself to being used as a diplomatic tool. That's not the modern Olympic Movement or who today's athletes are and what they want. Today's athletes are no longer a bunch of rich elitist people from mostly Western European countries. They're young people from all walks of life in this country and around the globe who are sacrificing everything to compete.

You can't care about and be proud of Team USA and at the same time want to keep the athletes from going to the most important competition of their lives. That's completely contradictory. I understand there are certain policies and enterprises the government has an absolute right to review and oversee. But a sporting event? It just doesn't make any sense.

Last question. Your passports are probably filled with as many entry and exit stamps as traditional diplomats. Through your status as an athlete, as an anti-doping ambassador, and as Chairman of the Laureus Academy – sport in effect made you a diplomat. Lots of people these days are cynical about the idea of sportspersons as statesmen and of sport as a force for global good. Are you?

No, not at all, because I've been able to use sports and garner the power of sports for absolutely the right reasons. I think I've been to 140 countries in my life now. The prestige of being a sports person who's known for more than just running around a track and jumping hurdles, to me, that means a lot and it's helped me to be effective in pursuing the causes I care about.

In addition to my posts at USADA and WADA, I was on the IOC athletes commission from 1981 through 1996, and I was the first American athlete to serve as a delegate to the IAAF. I'm proud to say I've been kicked off of a lot of boards and organizations over the years, because it was doing the right thing for the right reasons. Doing the right thing is not always the best thing for you personally, but nonetheless, you do it anyway. That's also Morehouse. We stand for what we really believe in and don't back down.

It's been a good run.