Eighth Annual Colloquium on Environmental Law and Institutions

|

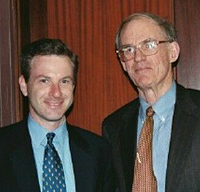

| Conference organizer Jonathan Wiener, left, professor of law, environmental policy and public policy studies, with co-author Richard Stewart, professor of law at NYU |

“Current climate policy has not been successful, environmentally, economically or politically. We need to rethink the incentives,” said Professor Jonathan Wiener, faculty director of the Center for Environmental Solutions and organizer of the event. “Our goals at the conference were to develop and discuss creative new options for climate change policy, foster interdisciplinary interaction about incentives, and identify key interdisciplinary research needs for future climate policy development.”

|

| Zhong Xiang Zhang, senior economist at the East-West Center, discusses incentives for China to participate in a global climate change treaty |

Duke Provost Peter Lange opened the conference, noting that the multidisciplinary focus on an important societal problem exemplifies the kind of initiative that Duke hoped to create through the three Centers co-sponsoring the conference. Underscoring the cross-disciplinary character of the collaboration, Dean William Schlesinger of the Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Director Bruce Jentleson of the Sanford Institute of Public Policy, MIRC Director and Political Science Department Chair Michael Munger, and Dean Katharine Bartlett of the Law School all welcomed participants.

The conference opened with a presentation of the new book by Wiener and New York University Law Professor Richard Stewart, Reconstructing Climate Policy: Beyond Kyoto (American Enterprise Press, 2003). After writing on climate policy for nearly 15 years, Stewart and Wiener argue that neither of the two options currently in view — either join Europe in the Kyoto Protocol now, or stay out and do nothing — is satisfactory. Based on the proposition that global climate policy must yield net benefits both globally and to each nation to attract its participation, they propose a new third option: the United States should engage China and other major greenhouse-gas-emitting developing countries in a new regime, parallel to Kyoto and with the possibility of eventual merger, that improves on Kyoto by making full use of international emissions trading and other market-based incentives; comprehensively embracing all greenhouse gases, sources and sinks; engaging participation by major developing countries; and setting targets based on maximizing net benefits. They recognize that this new regime would be difficult to create, especially if China perceives global warming as a potential benefit to its agriculture. But they argue that if properly designed it would prove attractive to China, to the U.S., and even to Europe.

|

| Kathryn Saterson, executive director of the Duke Center for Environmental Solutions, discussing incentives for developing country participation in climate change treaties |

Early in the conference, Stewart argued that this new approach would be more environmentally effective, less costly, and more politically successful than its alternatives. He emphasized the need for institutional learning — on policy design, on how best to motivate participation by major emitting countries, and on the value of experiments with plurilateral approaches rather than being locked into a single global regime.

Stewart’s talk set the stage for sessions on climate change impacts, optimizing climate policy over time, international emissions trading, and attracting participation by major developing countries. The conferees identified several priority issues for further research, including:

- The need for more integrated models that forecast both local and global effects and that predict national net benefits.

- The evolution of policy regimes over time, including questions of learning and path dependence.

- The goals of climate policy, such as avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference or maximizing net benefits.

- The motivations for participation by the U.S., China, and other major countries, and the role of policy instrument design in engaging such participation, such as through tradable allowance allocations.

- The challenges of monitoring and enforcement, including measuring non-point sources, keeping countries from defecting, ensuring compliance over several sequential allowance allocations, and the potential role of non-governmental organizations.

- The need to understand what drives technological change.

|

| Roni Avissar, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Duke University, discusses the effect of Amazon deforestation on global climate change |

As the conference concluded, MIRC Director Munger wondered whether governments ever will act vigorously on long-term problems such as climate change when politicians (at least in democracies) have short time horizons driven by reelection cycles. David Bradford of Princeton University emphasized the fundamental problem of producing a global public good such as climate protection in a world of autonomous states. In closing, Wiener pointed to the design of policy instruments for an international regime as a pivotal way to generate national net benefits and thus create incentives for global collective action. Stewart urged attention to cases in which global public goods had been successfully generated in the past, as lessons for the future.

The complete conference agenda, presentations and participant list are available at http://www.env.duke.edu/solutions/colloquia-8th.html.