Nick Galifianakis ’53 and John Semonche ’67

John Semonche ’67, left, and Nick Galifianakis ’53

John Semonche ’67, left, and Nick Galifianakis ’53

Nick Galifianakis ’53 and John Semonche ’67 have been talking about politics as friends and next-door neighbors in Durham for 46 years. Both Democrats, they met when Galifianakis was entering his third term in the U.S. House of Representatives, having earlier served three terms in the North Carolina General Assembly. Two years later, he was defeated in his race for the U.S. Senate by Republican Jesse Helms, whose savvy use of media (and money) and pugnacious campaign style helped usher in Republican dominance in the South.

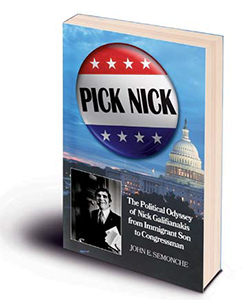

Semonche, now retired as a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has paid tribute to his friend’s considerable political success and the significance of that last campaign in a new book, Pick Nick: The Political Odyssey of Nick Galifianakis from Immigrant Son to Congressman (Tidal Press, 2016). In addition to paving the way for the “politics of fear” that has characterized recent election cycles, the 1972 race marked the ascendance of media as a tool of political warfare.

“Nick’s is a story about an individual in a changing world,” says Semonche. “Nick was the sort of ideal politician in the old mold of ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington’ and the old mold was breaking.”

Mr. G. goes to Raleigh — and then to Washington

The gregarious son of Greek immigrants who owned and operated the Lincoln Café on South Mangum Street in Durham, Galifianakis had been elected president of his undergraduate class at Duke but assumed that his unusual name might be a hindrance to his pursuit of higher political office. His friends disagreed; while he was teaching a course in business law at Duke as an attorney-instructor in 1960, 36 of his colleagues secretly contributed 50 cents apiece to cover the $18 filing fee and registered Galifianakis as a candidate for the state house of representatives. He took matters from there, introducing himself to local politicians and people of influence, to millworkers during their shift changes, and even to a farmer working his field on a tractor.

The gregarious son of Greek immigrants who owned and operated the Lincoln Café on South Mangum Street in Durham, Galifianakis had been elected president of his undergraduate class at Duke but assumed that his unusual name might be a hindrance to his pursuit of higher political office. His friends disagreed; while he was teaching a course in business law at Duke as an attorney-instructor in 1960, 36 of his colleagues secretly contributed 50 cents apiece to cover the $18 filing fee and registered Galifianakis as a candidate for the state house of representatives. He took matters from there, introducing himself to local politicians and people of influence, to millworkers during their shift changes, and even to a farmer working his field on a tractor.

In fact, Galifianakis was a natural, “old fashioned” politician who had a sense that any voters who met him would like him, Semonche says. During three terms in the General Assembly that coincided with the tenure of the progressive Gov. Terry Sanford, Galifianakis mastered legislative procedure. Legislation he introduced left an enduring legacy that includes Research Triangle Park’s focus on science and technology, the establishment of an administrative structure to support the state’s nascent community college system, and reforms that resulted in a uniform state-supported court system, informed by his work as a general practitioner in Durham County courts, in which justices of the peace and clerks were not lawyers. “The court system was horrifying,” Galifianakis says. “The prosecutions in Durham’s ‘Recorders Court’ were primarily of poor blacks who were inevitably found guilty and charged $30 and $50 fines, which was horrifying.”

Having gained a reputation as an effective legislator, Galifianakis ran successfully for Congress in 1966. In that race and two that followed, he relied on a tireless meet-and-greet style and a sense of fun, campaigning with flatbed trucks of dancers, treating voters to baseball games, and deploying inventive buttons and jingles to ensure they remembered his unusual name.

In Washington, he sought to improve federal programs, such as housing for poor urban residents and, as a member of the Banking and Currency Committee, he tried to tackle some questionable practices of the rapidly growing credit-card industry. A Marine Corps veteran, Galifianakis became the first member of the North Carolina delegation to oppose the Vietnam War and to voice his opposition to the draft. He also broke with the state delegation on the Equal Rights Amendment, explaining to Sen. Sam Ervin that he not only supported women in their quest for equality, but that his wife, Louise, would be extremely upset if he voted against it.

Galifianakis, left, brought an entertaining style to the campaign trail.

Galifianakis, left, brought an entertaining style to the campaign trail.

In 1968, Galifianakis received a special visit on the House floor from the newly elected president, Richard Nixon ’37, who wanted to meet his fellow Duke Law graduate. Multiple invitations for dinner at the White House followed, as were rides home on Air Force One whenever the president was headed to North Carolina. (Galifianakis was surprised and dismayed when Helms’ 1972 campaign posters carried an admonition from President Nixon that “I need Jesse Helms in Washington.”)

Semonche points to bipartisanship as a hallmark of his friend’s political career. “Nick respected members of the other party,” he says. “He saw that politics was really the art of compromise, and you may have your views, but those views were really always subject to change on the basis of intelligent input from the other side.”

Confronting the changing South

With redistricting putting his House seat in continual jeopardy, Galifianakis decided to run for the Senate in 1972, and unseated a longtime incumbent, Sen. B. Everett Jordan, in the Democratic primary. Helms, a prominent radio and television commenta- tor known for his virulent anti-communist rhetoric, had long targeted Galifianakis for his opposition to the Vietnam War. Except for national defense, Helms opposed all federal government action — he characterized affirmative action as reverse discrimination — and advocated for a “spiritual rebirth” of the country.

Determined to run a positive campaign, Galifianakis maintained his personal and personable style of connecting with voters. He traveled the state in a motorhome named “Miss Sophie,” in honor of his mother, believing, Semonche says, that person-to-person contact would always be more effective than media outreach. On Oct. 3, he led Helms in polling, 51 percent to 28 percent.

A month later, though, the tide had turned against Galifianakis. Helms out-raised him and poured millions into radio and television advertising, a relatively innovative strategy for the time, Semonche says. “Nick and I have argued at times at how much money was a factor in the election of 1972,” Semonche says. “It’s not money as such, but what money buys: control of your ability to characterize your opponent and put your opponent on the defensive.”

By Nov. 3, Galifianakis trailed by 10 percentage points and he ultimately lost to Helms by eight, despite receiving almost 90 percent of the African American vote.

While he refused to debate Galifianakis, Helms characterized his opponent as being not only too liberal to represent a conservative Southern state, but as alien. His campaign slogan was “Vote for Jesse Helms: He’s one of us,” implying that Galifianakis wasn’t.

“It meant a few things: he’s too liberal, he’s not a Southerner, and he’s not Southern Baptist,” Semonche says. “He doesn’t have a name like those of other Southern politicians. These things would be nonsensical to anyone who had come into contact with Nick, but Nick couldn’t come into contact with all the voters in the state.” Galifianakis, who was nationally prominent among members of the Greek Orthodox faith, goes further, saying the slogan implied that he was not, in fact, Christian.

Helms’ approach to campaigning in 1972, which he perfected over another four successful runs, was the beginning of a lasting change that persists today, says Semonche. Helms introduced an “evangelistic fervor” to the conservative movement that framed social and economic issues as an important rallying point and heightened the party’s ties to a religious base.

“Jesse Helms and the campaign apparatus that he built was really an important part of the foundation of the modern Republican Party,” says Semonche, who ties the Galifianakis-Helms race to the current political landscape. “Negative campaigning works, and the sooner it’s employed the better. Positions on issues and experience are of lessening importance — and we’ve certainly seen that to be true in 2016, as money has become increasingly important because of the expense of media advertising and using the media to fix the image of one’s opponent.”

Semonche, who specializes in constitutional history and the Supreme Court and pursued his JD at Duke while teaching full-time at UNC, aimed to highlight more than just the ongoing significance of Galifianakis’s loss to Helms with Pick Nick. “There was more to Nick’s political career and his political style that may be past, but is still appealing,” he says.

Semonche, who specializes in constitutional history and the Supreme Court and pursued his JD at Duke while teaching full-time at UNC, aimed to highlight more than just the ongoing significance of Galifianakis’s loss to Helms with Pick Nick. “There was more to Nick’s political career and his political style that may be past, but is still appealing,” he says.

After leaving politics, Galifianakis returned to the practice of law in Durham, taking every kind of client and case that came his way until finally retiring in his mid-80s. Even at 88, Semonche writes at the end of the book, Galifianakis is “stopped by people who remember his time in politics, some of whom can still sing his campaign song in its entirety.”

— Frances Presma