PUBLISHED:December 07, 2011

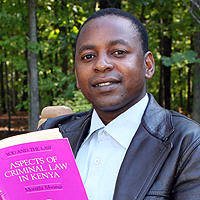

Solomon Njeru LLM '12

For Solomon Njeru, it was a long road from his home village of Ruungu, in arid east Kenya, to the teeming city of Nairobi, where he practiced corporate law before becoming a homicide prosecutor. A Ford Foundation grant has helped him take a considerably less arduous trip to Duke Law, where he is pursuing an LLM, broadening his perspective and honing his legal skills in hopes of becoming a better prosecutor and more effectively pursuing his passion, human rights advocacy.

“I come from a very poor community and family, and the issue of human rights to me is personal,” says Njeru. “We have been persecuted as a community, we don’t have land rights. I have seen the issue of human rights really affect people. That really shaped my thinking.”

Despite having few means and nine siblings, Njeru was able to work his way through school and into a law firm, he says.

Ruungu is in a part of Kenya where jobs, water, and food are scarce. “It is by the grace of God that I got an education,” says Njeru, who has nine siblings and worked to help pay for his secondary and university education. He and other educated villagers from Ruungu have formed a group to improve conditions.

“With our little money we have been able to educate some of the children,” he says. “People there mostly have to rely on government relief for food, so we had the idea of irrigating the village. We dug the trenches ourselves, and at least the village now has water. Many villagers can now feed themselves.”

Njeru’s commitment to service extends to his membership in an informal group of lawyers doing rights-based outreach in poor communities across Kenya.

“I also work with prisoners to teach them their human rights, and in the town where I work, I link with childrens’ offices to assist juvenile offenders,” he adds. “In Kenya we have a problem with juvenile offenders, and I help young people and get them placed in childrens’ homes.”

Njeru, who plans to continue human rights advocacy on his return to Kenya, says his Duke Law experience is helping shape his perspective.

“My classes and the Duke Human Rights Society have touched on transition of justice issues in post-conflict countries,” he says, noting that Professor Laurence Helfer’s class on International Law is a favorite. “This is the most pressing problem in Kenya. We changed our constitution just last year, but before that, there were so many abuses. For instance, we’re trying to address land rights issues and also to get justice for the victims of intertribal violence that occurred before the 2007 election. Six of our leaders are facing International Criminal Court charges, but there are other people who we have to prosecute in Kenya.”

Tribal identity makes arresting and trying war criminals difficult and also allows politicians to affect legal outcomes by playing on tribal loyalty, Njeru says. It’s a situation he and others have been working to change. “We are trying to push is the independence of the judiciary. And we are trying to sensitize and educate them to the fact that when we arrest a wrongdoer, it’s not their community or tribe we’re punishing.”

Njeru says rights activists often find themselves competing with political forces as they attempt grassroots education. “It’s very hard to get people to understand what they’re entitled to from a legal point of view, especially when there are politicians who want something different. And the politicians have bigger, better ways of communicating than human rights advocates.”

At Duke the new Custom and Law seminar is helping Njeru get a fresh perspective on Kenyan law.

“I come from a country where custom is custom, I’ve never gone through a system where you examined specific customs as they applied to specific legal subjects,” he says. “It’s an exceptional class, and it has made me think of the Kenyan customs. We have 42 tribes with different customs. I wonder, ‘How would I apply those customs to teaching and advocating for human rights?’”

“I come from a very poor community and family, and the issue of human rights to me is personal,” says Njeru. “We have been persecuted as a community, we don’t have land rights. I have seen the issue of human rights really affect people. That really shaped my thinking.”

Despite having few means and nine siblings, Njeru was able to work his way through school and into a law firm, he says.

Ruungu is in a part of Kenya where jobs, water, and food are scarce. “It is by the grace of God that I got an education,” says Njeru, who has nine siblings and worked to help pay for his secondary and university education. He and other educated villagers from Ruungu have formed a group to improve conditions.

“With our little money we have been able to educate some of the children,” he says. “People there mostly have to rely on government relief for food, so we had the idea of irrigating the village. We dug the trenches ourselves, and at least the village now has water. Many villagers can now feed themselves.”

Njeru’s commitment to service extends to his membership in an informal group of lawyers doing rights-based outreach in poor communities across Kenya.

“I also work with prisoners to teach them their human rights, and in the town where I work, I link with childrens’ offices to assist juvenile offenders,” he adds. “In Kenya we have a problem with juvenile offenders, and I help young people and get them placed in childrens’ homes.”

Njeru, who plans to continue human rights advocacy on his return to Kenya, says his Duke Law experience is helping shape his perspective.

“My classes and the Duke Human Rights Society have touched on transition of justice issues in post-conflict countries,” he says, noting that Professor Laurence Helfer’s class on International Law is a favorite. “This is the most pressing problem in Kenya. We changed our constitution just last year, but before that, there were so many abuses. For instance, we’re trying to address land rights issues and also to get justice for the victims of intertribal violence that occurred before the 2007 election. Six of our leaders are facing International Criminal Court charges, but there are other people who we have to prosecute in Kenya.”

Tribal identity makes arresting and trying war criminals difficult and also allows politicians to affect legal outcomes by playing on tribal loyalty, Njeru says. It’s a situation he and others have been working to change. “We are trying to push is the independence of the judiciary. And we are trying to sensitize and educate them to the fact that when we arrest a wrongdoer, it’s not their community or tribe we’re punishing.”

Njeru says rights activists often find themselves competing with political forces as they attempt grassroots education. “It’s very hard to get people to understand what they’re entitled to from a legal point of view, especially when there are politicians who want something different. And the politicians have bigger, better ways of communicating than human rights advocates.”

At Duke the new Custom and Law seminar is helping Njeru get a fresh perspective on Kenyan law.

“I come from a country where custom is custom, I’ve never gone through a system where you examined specific customs as they applied to specific legal subjects,” he says. “It’s an exceptional class, and it has made me think of the Kenyan customs. We have 42 tribes with different customs. I wonder, ‘How would I apply those customs to teaching and advocating for human rights?’”