Wilson Center research team finds promising results in pre-arrest diversion program for people who use drugs

Active participants in Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion were significantly less likely to be re-arrested and more likely to use behavioral health treatment, according to a study of four programs in North Carolina.

Associate Professor Allison R. Gilbert PhD, MPH

Associate Professor Allison R. Gilbert PhD, MPH

Participants in a pre-arrest diversion program in North Carolina for people who use drugs had substantially fewer arrests after enrollment and were more likely to utilize behavioral health resources, according to researchers from the Duke University School of Medicine.

People who actively participated in Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) had a 50% lower rate of citations or arrests in the six months after referral than the six months prior, according to an evaluation of four NC LEAD sites released in January 2023.

Additionally, 71% of LEAD enrollees utilized behavioral health services in the year after joining the program, compared to only 34% in the year prior, and the number of enrollees using medications for treating opioid use disorder (also known as medication-assisted treatment or MAT) quadrupled. Behavioral health service utilization varied quite widely across programs. That may have been influenced, in part, by the availability of behavioral health resources and treatment infrastructure across the different communities.

“Our evaluation shows promising criminal justice and service utilization outcomes among participants who consistently engaged with LEAD staff, as well as potential cost savings for crisis-related services like behavioral health-related emergency department visits for those localities with a LEAD program,” said Allison R. Gilbert, PhD, MPH, principal investigator for the project.

“In evaluating the program sites in North Carolina, we were also able to identify factors that facilitated successful implementation of LEAD programs and recommend ways to overcome barriers to enrollment and continuous engagement.”

North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein said the Duke team’s research confirms that criminal justice diversion programs can work.

“LEAD programs move people with substance use disorder out of the criminal justice system into the health care system where they can get well. In the process, they make communities safer and save taxpayers money because people in treatment and recovery are less likely to commit crimes,” Stein said.

“I hope this important research inspires more agencies to implement diversion programs, using either opioid settlement funds or other sources of funding. These programs must treat everyone equally and not disadvantage people on the basis of race or gender.”

LEAD is a community-based, pre-arrest criminal justice diversion program that connects people who use drugs and are at risk of arrest for low-level unlawful conduct with support services such as social and medical services, behavioral health treatment, and harm reduction resources. Police officers can use their discretion to refer eligible individuals to LEAD either as an alternative to arrest and prosecution or simply because the officer believes an individual could benefit from the program.

Gilbert, an associate professor in the School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, led the multi-site evaluation of the LEAD sites by a team that also included study coordinator Reah Siegel, MPH, postdoctoral associates Josie Caves Sivaraman, PhD, and Meret Hofer, PhD, and co-investigators Michele M. Easter, PhD, an assistant professor in the department, and professors Marvin S. Swartz, MD, and Jeffrey W. Swanson, PhD. All are affiliates of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law, which co-funded the project.

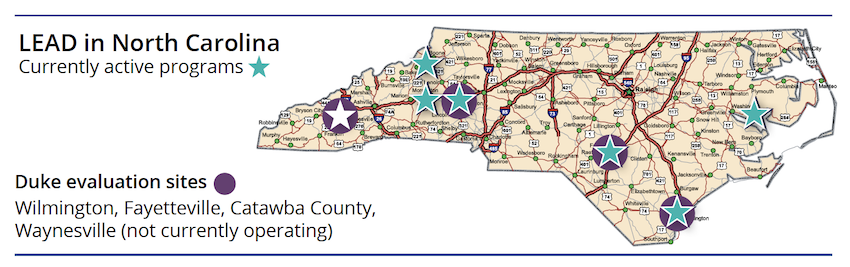

Between 2019 and 2022, the team interviewed participants, police officers, and program partners and analyzed administrative records and criminal justice data at four North Carolina LEAD sites in Fayetteville, Wilmington, Catawba County, and Waynesville.

Key findings include:

- Across all sites, the rate of citations or arrests for consistently engaged LEAD participants dropped by 50% during the six months after referral compared to the six months prior.

- Criminal justice outcomes improved for participants in the LEAD program regardless of their level of engagement with LEAD staff, compared with people with similar drug charges who were eligible but not referred. The rate of citations or arrests for people referred to LEAD fell by one-third in the six months after referral compared to the prereferral period.

- While only 34% of LEAD enrollees utilized behavioral health outpatient services before their referral, 71% did so in the year following their enrollment – a 48% increase in utilization.

- Utilization rates of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) also rose. In the year prior to joining LEAD, 3% of enrollees had a MAT visit with a provider, averaging 3.7 visits per person. In the year after, 12% of enrollees had a MAT visit, averaging 72.5 visits per person. Among those not enrolled in LEAD, MAT rates stayed about the same.

- Crisis-related service costs dropped by about 50%, on average, for each program site in the study (an average $2,282 per person in the year before LEAD to an average $1,136 per person after LEAD).

Gilbert said a key factor in participant outcomes was level of engagement with LEAD staff, with the most significant positive impacts occurring among participants who maintained medium or high levels of contact with staff following referral.

“LEAD staff provided program participants consistent and non-judgmental emotional and logistical support to navigate life challenges in a unique way not typically provided by other people in their social networks,” Gilbert said. “While it may not be the only factor, the association between consistent engagement and positive outcomes appears to have been an essential driver of the programs’ benefits.”

All stakeholder groups—including program participants—strongly valued their LEAD programs, and many wanted to expand their programs’ reach. However, they identified barriers to referral such as restrictive eligibility requirements related to criminal history that precluded referrals for some people who could benefit, and low awareness or buy-in to LEAD among some law enforcement officers. Once referrals were made, there were also barriers to enrollment in the program, including when “warm hand-offs” between referring officers and program case managers were not possible, and unclear messaging during referrals that may have led prospective participants to inaccurately believe the program imposed treatment requirements.

LEAD referrals and enrollments were disproportionately composed of females (60%) and white people (83%) as compared to the demographics of people charged in the programs’ jurisdictions with the type of drug possession and paraphernalia charges that are eligible for LEAD diversion, indicating the need for more targeted outreach to communities color and more inclusive eligibility criteria.

The project’s final report recommends adequate funding to support full-time dedicated LEAD staff engaged in field-based outreach. Researchers also suggest programs can be scaled up by holding regular trainings for police officers, expanding eligibility for the program to increase referrals, improving the rate of post-referral enrollment and engagement through field-based outreach, and encouraging and strengthening participant and community engagement.

First developed in Seattle in 2011, LEAD programs have been implemented at 52 sites nationally, with another 44 sites in various stages of development. Other sites have shown similar positive results: participants in Seattle’s LEAD program were 58% less likely to be arrested after enrollment compared to non-enrollees, according to program data.

More information on the project is available at https://wcsj.law.duke.edu/projects/.