Wrongful Convictions Clinic client freed after serving nearly 24 years for a crime he didn’t commit

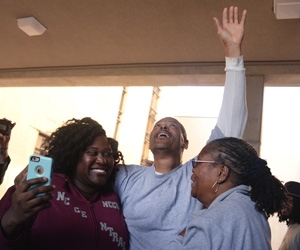

Howard Dudley with family <br />(Photo: Zach Frailey, The Kinston Free Press)

Howard Dudley with family <br />(Photo: Zach Frailey, The Kinston Free Press)

A courtroom in Kinston, N.C., erupted in applause on March 2, when a judge ordered Howard Dudley’s release from prison after 23 years of incarceration for a crime he didn’t commit.

Dudley, a client of the Duke Law Wrongful Convictions Clinic, had been convicted in 1992 of sexually assaulting his then 9-year-old daughter. He said he will never forget hearing Superior Court Judge W. Douglas Parsons call that conviction “an injustice.” Having always maintained his innocence, Dudley had rejected a 1992 plea deal and several parole options, because they required an admission of guilt. “I am not a child molester,” he told reporters after his hearing. “I have never been one and I will never be one.” His daughter, Amy Moore, who testified on his behalf, also has been insisting on his innocence since shortly after his conviction.

Grady Champion ’16, who worked on Dudley’s case over two semesters in the Wrongful Convictions Clinic and attended the hearing, said the judge’s order “demonstrated the very real power of the law.”

“When the judge started speaking, our client had shackles around his feet,” Campion said. “When the judge finished, those shackles came off.”

“An injustice”

Parsons cited several reasons for invalidating the initial verdict, including the fact that Dudley’s first attorney never received documents noting social workers’ doubts about the veracity of his daughter’s allegations, including doubts expressed by the guardian ad litem appointed to represent her best interests. Further investigation by clinic students and lawyers uncovered some of the psychological and mental impairments suffered by Dudley’s daughter, further calling into question her testimony against him. Parsons said that her testimony was not believable. The judge also criticized Dudley’s first trial attorney, who had only been practicing law full-time for a year, had little felony trial experience, and who did not file any motions or consult any expert witnesses.

In 2005, the Raleigh News & Observer published a series of articles revealing problems with Dudley’s case and calling the verdict into question. The case was then investigated by the North Carolina Center for Actual Innocence, an independent non-profit that preliminarily screens inmates’ requests for assistance. Finding it worthy of serious review, they referred it to Wrongful Convictions Clinic.

Kim Chemerinsky ’07, then a clinic fellow, worked on the case for two years, after which teams of students enrolled in the clinic worked with clinic co-director Theresa Newman and supervising attorney Jamie Lau ’09 to build the elements of a post-conviction relief motion that could lead to a new hearing.

Lau, who argued at the March hearing alongside Raleigh attorney Spencer Parris, said the Social Services documents and Dudley’s daughter’s medical and psychological records clearly exposed the problems with his trial.

“Those two things provided us the paper trail which allowed us to demonstrate just how ineffective the attorney was as well as the Brady violations — the constitutional violations with respect to the material the state should have known it never provided at the time of the trial,” Lau said.

Among the student contributions to Dudley’s Motion for Appropriate Relief, those of Larissa Boz ’14 and Courtland Tisdale ’14 were critical, said Newman, noting that Tisdale entered law school after completing a PhD in clinical psychology. “The two of them, Court in particular, brought to this case what was necessary to the unraveling of it: an understanding of Mr. Dudley’s daughter’s complicated psychiatric and psychological health,” Newman said. “Larissa brought a keen understanding of what needed to get done during the investigation stage of our work and applied her prodigious energy to doing it.”

Forty minutes, four witnesses, life in prison

Prof. Jamie Lau '09 shaking hands with Howard Dudley.

Prof. Jamie Lau '09 shaking hands with Howard Dudley.

(Photo: Chris Seward, News & Observer)

Dudley had been charged and prosecuted in spite of numerous “red flags” raised during the initial police investigation, Lau said.

“A police officer who first heard the allegations reported them to the Department of Social Services, and he reported that Dudley’s daughter didn’t seem traumatized or upset at all, her mother was doing all the talking for her, there was an ongoing dispute between the parents for child support,” Lau said. “I mean, everything he said to DSS was a red flag but it’s not in any of law enforcement’s reports or it’s not followed up on in any meaningful way. The entire investigation by the Kinston Police Department was four interviews that spanned 40 minutes.”

“Jamie said that at the hearing, and it was powerful” Newman said. “‘Forty minutes, four witnesses.’ And life in prison.”

Campion and Evan Glasner ’16 were the lead students on the case at the time of Dudley’s rehearing, having worked on it through the fall clinic semester and in the spring as advanced clinic students.

Both will be joining litigation practices in New York after graduation and say the Dudley case offered unique preparation and a strong sense of satisfaction.

“Working on this case was a great experience in learning how to gather facts and prepare for a court proceeding,” Campion said. “Our primary task was to line up the facts and witnesses to support our various arguments why Mr. Dudley’s conviction should be vacated. We researched and interviewed expert witnesses. We made a number of trips to eastern North Carolina to interview fact witnesses and prepare them to testify at trial. We visited and wrote to our client to keep him updated on the status of his case.”

The practical experience provided in the clinic was invaluable, both students say, but the case’s conclusion was unforgettable.

“My motivation for joining the Wrongful Convictions Clinic was to gain some practical litigation experience while doing some truly meaningful work,” said Glasner, who admitted it hard to hold back tears of joy when the judge announced Dudley’s exoneration. “While this was the first verdict that I have been intimately involved in, I find it difficult to imagine that any future decision will feel as good.”

Glasner, Campion, Boz, and other members of Dudley’s legal team joined him and his family at a Kinston Bojangles for his first meal after nearly 24 years in prison.

In a telephone interview a week after his release, Dudley called Parris, Newman, Lau, and the clinic students “awesome.”

He said he had faith that his name would be cleared, but did not expect the judge’s decision to be so quick or decisively worded.

“What he had to say, it will always be branded in my mind,” Dudley said. “It was important to me that the public got a chance to hear what I heard and see what I saw, from the perspective of someone who had the authority to set me free.”

Dudley said one of the judge’s statements was particularly moving to him.

“When he looked over at me and he’s saying that the system failed me, that’s the part right there.”

Howard Dudley with family, friends, and members of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic.

Howard Dudley with family, friends, and members of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic.

(Photo: Chris Seward, News & Observer)